The Christian War on Death

How Christianity reframed mortality and unleashed biotech acceleration.

By Ian Huyett

“God created man for incorruption, and made him in the image of his own eternity.”

-Book of Wisdom 2:23

In 313 AD, the Roman general Constantine conquered his rivals in a civil war, culminating in a famous victory at the Milvian Bridge. Before the battle, Constantine experienced a vision instructing him to paint the Christian symbol “chi rho”— ☧—on his men’s shields. His Edict of Milan ended official persecution, legalized Christian worship, and allowed the Christian church to own property, unleashing Christianity’s messianic energies from Anatolia to Britain.

While Constantine’s reforms made Christianity the dominant religious, cultural, and economic institution in the West, the emperor rejected forceful conversions. In a follow-up edict, he clarified that Christians must “voluntarily… undertake the conflict for immortality.” In his book Defending Constantine, Christian scholar Peter Leithart translates Constantine’s statement as “The battle for deathlessness requires willing recruits.”

Christianity’s New Conception of Death

The Emperor’s turn of phrase was significant. Christianity was suffusing the classical world with a fundamentally new conception of mortality as an aberration, a trespasser in creation, and a kind of illness afflicting the cosmos. The Western mind had come to see sickness, decay, and death itself as enemies to be fought, conquered, and destroyed.

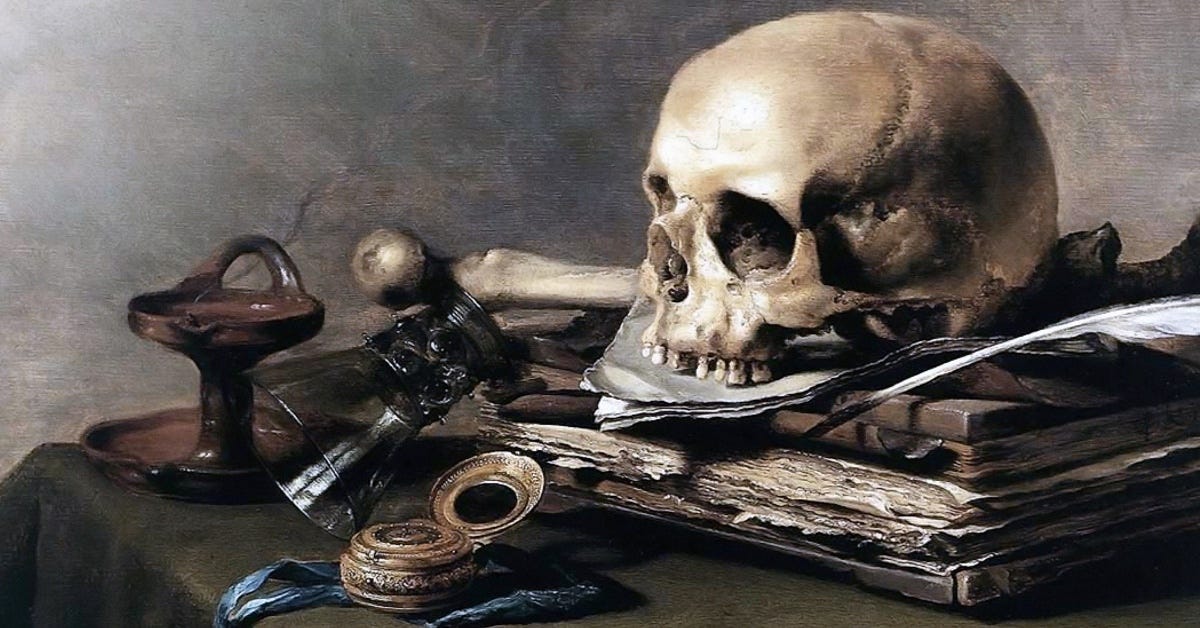

Pre-Christian antiquity saw death as a value-neutral reality ordered by the fates. In the Iliad, Hera mocked Zeus for thinking he could save a man from his fated doom; mortality was a boundary even the gods were foolish to resist. Cicero affirmed that “if the soul did perish, there would be, even then, no evil in death.” Marcus Aurelius exhorted us to “[wait] for death with a cheerful mind, as being nothing else than a dissolution of the elements of which every living being is compounded… For [death] is according to nature, and nothing is evil which is according to nature.”

Contrast these sanguine ancients with the messianic monotheism radiating from Judea. Anyone who searches for “death” in the Bible will find himself hard-pressed to find one charitable word about mortality. From start to finish, the Bible is fanatically consistent in its view of death as an unalloyed evil, foreign to our created nature, and the great enemy of humanity and God.

Editor’s note: The following is a very comprehensive exegesis for readers interested in deep analysis of the Bible. If that’s not you, feel free to skim a bit down to “Death Gives Life Meaning” and the Pro-Aging Trance.

You can open the Psalms and pick any reference, at random, to “death” or “Sheol [the grave]” and you will find the Psalmist praying for salvation from death—not reconciliation to his own dissolution. Psalm 118, a cornerstone of all Christian liturgy, prefigures the resurrection: “I shall not die, but I shall live, and recount the deeds of the Lord.”

The Psalms of David, in particular, display this theme. Psalm 16 says: “You will not abandon my soul to Sheol [the grave] / or let your holy one see corruption. You make known to me the path of life / in your presence there is fullness of joy.”

Death is evil because the grave represents disintegration and oblivion. “What profit is there in my death?... Will the dust praise you?” David asks God. As surely as death is evil, longevity is good. “He asked life of you; you gave it to him / length of days forever and ever,” says Psalm 21.

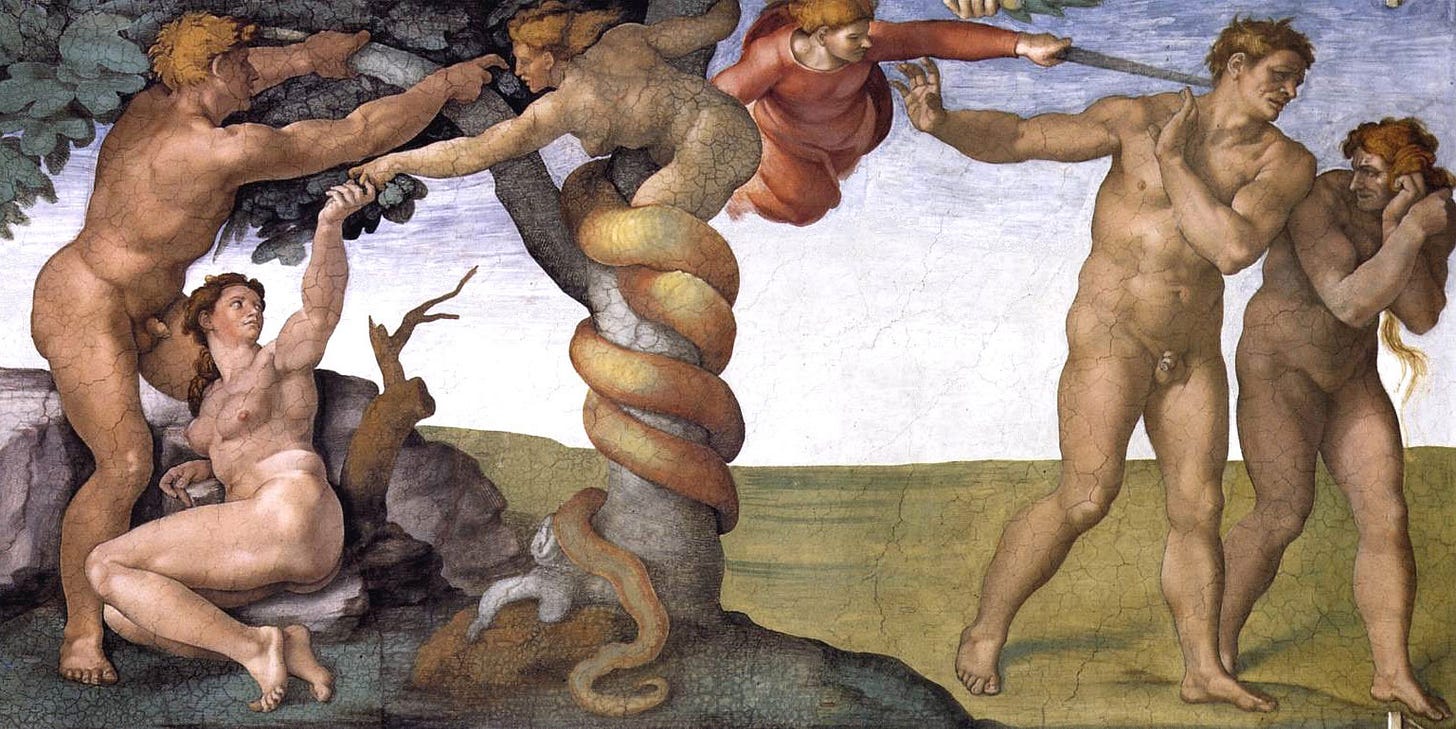

The Book of Genesis explains the introduction of death into the world through the story of Eden and the Fall of Man. Only one tree in the Garden of Eden, the “tree of knowledge of good and evil,” was forbidden to man. Yet the fruit of a different tree, “the tree of life,” was expressly given to Adam and Eve to eat. The fruit of this tree of life could sustain human life indefinitely, enabling us to “live forever.”

Tempted by Satan, human beings rebelled against God by eating from the “tree of knowledge of good and evil.” By rejecting the order of Eden, humans lost access to the tree of life. Sickness, deformity, and decay—all things that were not part of God’s design—entered into the world. Humanity was consigned to deteriorate back into the dust from which it was originally created.

The first-century BC Book of Wisdom, while regarded as apocryphal by Protestants, accurately summarizes the Bible’s overall view of death as an intruder that does not belong in creation: “God created man for incorruption and made him in the image of his own eternity, but through an adversary’s envy death entered the world.”

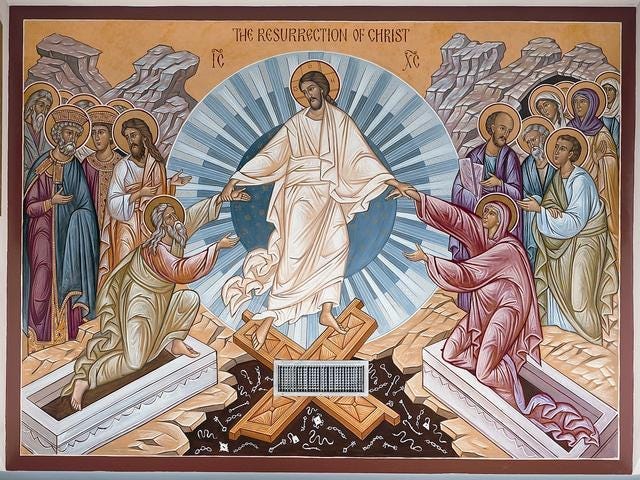

Taking up these themes, the biblical prophets prophesied the defeat of death, to be replaced with “everlasting life” for those whose names are written in God’s book of life. The prophets describe a physical, bodily resurrection of the dead from the dust: “You shall know that I am the Lord, when I open your graves, and raise you from your graves.”

Throughout the Old Testament, death is consistently held up for scorn as the evil that God hates most. The word “death” is used as a stand-in for all the evil in the world. Wisdom, personified as a woman in the Book of Proverbs, says “all who hate me love death.” God pleads in vain with his people, Israel, to turn from their self-destruction and avoid death. “I desire not the death of the wicked, but that the wicked turn from his way, and live… why will you die, O house of Israel?”

The first Christians believed that Christ came into the world so that death might be defeated. Christ is called the “New Adam,” for “as in Adam all die, so also in Christ shall all be made alive.” The apostles celebrated the coming, corporeal conquest of death, the “Last Enemy to be Destroyed.” Paul taunted death: “Death is swallowed up in victory. ‘O death, where is your victory? O death, where is your sting?’”

Finally, Revelation foretells that death will bechucked into the apocalyptic “lake of fire” with the devil—that death itself will die. In a restored and glorified material universe, “death shall be no more.” The “water of life” will then be given freely, and the “tree of life” from Eden will be restored.

Human beings, far from being passive observers, will actively co-participate with God in working towards this future. “The one who conquers will have this heritage [the water of life and immortality],” God announces in Revelation 21, “and I will be his God and he will be my son.” Revelation 2 clarifies that this “one who conquers” is not Christ, but the human reader of the book—who Christ is inviting to wield power “as I myself have received authority from my Father.”

The Bible contained the foundations of Constantine’s “battle for deathlessness.” Christianity rejects any attempt to cast death as a neutral fact of life or a positive good. It also stands in opposition to the modern idea that “death gives life meaning,” for the Bible is clear that death has no redeeming features and can never be a positive good to conserve. Instead, the Christian revelation reconceptualizes death as purely evil—the ultimate evil, in fact—and an unacceptable defect in the world. God, with the co-participation of his people, will destroy it entirely.

The apostles, and centuries of Christians thereafter, stood ready to face death for Christ. Yet Christian martyrdom can only be understood in the light of the promised bodily resurrection and new creation.

The Apostle Paul was as cold and sober as Bertrand Russell in recognizing that death, if it has the last word, entails nihilism. Without the resurrection of the dead, Paul says, “your faith is in vain.” The Christian martyrs did not die to welcome Marcus Aurelius’ cheerful dissolution, but to rise from their graves and live again. The Catholic thinker G.K. Chesterton aptly contrasted the martyr and the suicide by saying that the martyr dies for the sake of life, while the suicide dies for the sake of death.

“Death Gives Life Meaning” and the “Pro-Aging Trance”

Today, it’s common to hear people claim that death adds value to our lives. While Elon Musk argues that death is necessary to create ideological turnover, the usual argument is that looming decay and oblivion gives our lives their urgency, focus, and fullness. For example, philosopher Simon Critchley, citing Cicero, criticizes longevity research by saying that “The one thing that gives life meaning is the certainty of death.”

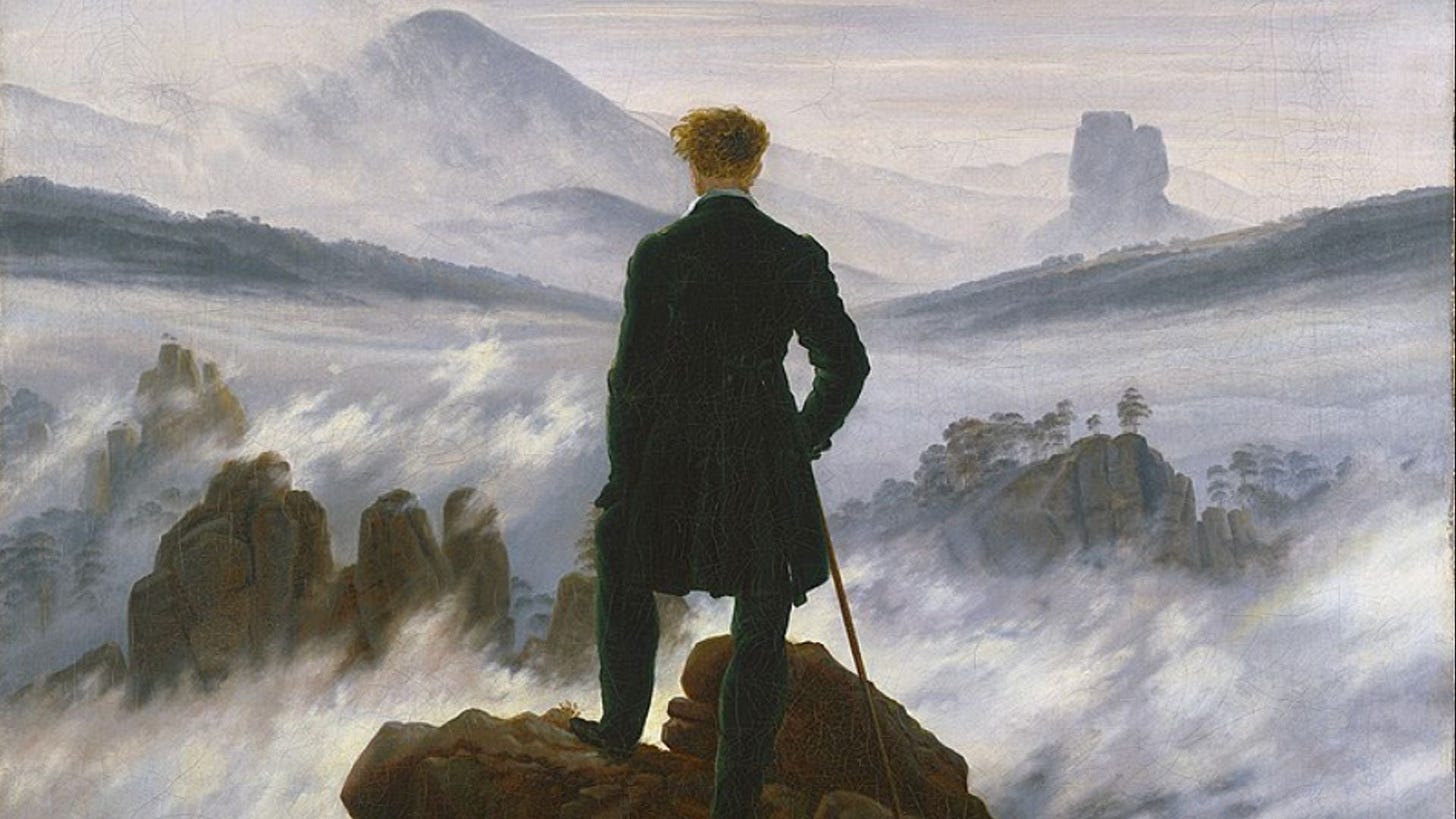

Modern novelists have been especially attracted to the idea that that life’s meaning comes from its being ephemeral and short. J.R.R. Tolkien, drawing from Wagner’s operas rather than the Bible, made death the “Gift of Ilúvatar,” the remote Prime Mover of a Neoplatonist cosmogony—a blessing which makes mankind special and offers us an escape from the material world. While the biblical Satan introduced death through the Fall of Man, Tolkien’s devil figure, Morgoth, tempts men with the prospect of release from death.

To give a more recent literary example, popular novelist Matt Haig imagines an immortal alien who is envious of human romantic love, which he says can “only be possible in someone who was going to die at some point in the future.”

Despite Christianity’s deep-seated hostility to death, non-Christian scientists and thinkers like Aubrey de Grey and Nick Bostrom are today’s leading critics of this view.

De Grey, a biogerontologist who pioneered the modern, engineering-based approach to aging as the progressive accumulation of specific categories of damage, has long described the notion that dying of aging “gives life meaning” as a “pro-aging trance.” De Grey posits that, if aging seems beyond the reach of medicine, “it makes good psychological sense to find some way to convince oneself that aging is all for the best.” As an example of this phenomenon, de Grey once cited the 2003 US President’s Council on Bioethics, which suggested that “our dedication to our activities [and] our engagement with life’s callings” depends on our looming mortality.

In his short story The Fable of the Dragon-Tyrant, philosopher Nick Bostrom satirizes these pro-death cliches by describing a world in which 10,000 people per day are fed to a giant dragon. Bostrom imagines pompous ethicists using identical arguments to defend the dragon sacrifices, even warning that a “preoccupation with killing the dragon” will distract us from the full enjoyment of our lives.

The notion that “death gives life meaning” can be answered by reflecting on common human experience. In law school, my textbook on wills, trusts, and estates began by observing that most people die intestate, or without a will. Why is this?

One answer is found in Leo Tolstoy’s short story The Death of Ivan Ilyich. Tolstoy imagines a character, Pyotr, attending the funeral of his friend, Ilyich. Tolstoy writes that Pyotr views the funeral “as if death was an occurrence proper only to Ivan Ilyich, but not at all to him.”

Most readers find that Tolstoy’s story illuminates a shared human experience of death—even when it confronts us at a funeral—as a remote abstraction. While Pyotr does not think “I will live forever,” this does not mean he genuinely has the belief that “I will die.”

The truth is that most human beings, including most intellectuals, lack the belief that they will have an individual, first-person experience of dying. While they appreciate that life is abstractly finite in duration, they have never beheld what Tolstoy called the ultimate truth: “day and night going round and bringing me to death.” As the author William Saroyan put it, “everybody has got to die, but I have always believed an exception would be made in my case.”

Do the countless people who die intestate today, or who empathize with Pyotr in Ivan Ilyich, live lives without true love or meaning? Teenagers, as most of us recognize in retrospect, find their own deaths more or less unthinkable. Are teenagers’ lives devoid of purpose—or of love?

“Death Gives Life Meaning” is a Secular Argument

The cliché that “death gives life meaning” seems to be no more than one or two centuries old. It originated, as far as I can tell, in the same place that Tolkien likely found it: in German romantic pessimism. Having read thinkers from every era of Christian and Western history, I have never found anything quite like it before Schopenhauer and after Constantine.

Some atheist futurists, recognizing the absurdity of the “pro-aging trance,” assume that the trance originated from Christianity. Nothing could be further from the truth. Of the 30,000 verses in the Bible, not one of them says anything approaching “death gives life meaning.” The prophets certainly never called death—as Tolkien suggests it was—“the Gift of the Lord,” nor waxed fondly about dissolution and oblivion like the Epicureans and Stoics. On the contrary, it was the Christian worldview that introduced the wholly opposite conception of death into the world.

An unsympathetic Christian reader, seeking to salvage a pro-death perspective, might claim that, although the biblical authors never said anything like “death gives life meaning,” they would have agreed with the sentiment if they lived today. A pro-death Christian might urge that the biblical authors could not foresee modern biotechnology and therefore were not motivated to warn us that longevity is bad.

But the state of science in antiquity tells us nothing about Christianity’s view of death. Homer, Cicero, and Aurelius could no more foresee cellular biology than the Psalmist could. Yet the Psalmist, not these Western classical authors, offered a strikingly unblinking, sober recognition of death as an absolute evil.

Nor did any significant Christian thinker in antiquity, the Middle Ages, or modernity—until about the past century—criticize any medical advancement on the grounds that it reduced sickness and suffering or forestalled death. When, for example, microbiologist and outspoken Christian Louis Pasteur successfully developed a vaccination for rabies in 1885, no theologian denounced Pasteur on the grounds that his vaccine would prolong millions of lives. On the contrary, Christian theologians from Gregory of Nyssa to Pope Pius XII have heralded technology and medicine as means of extending mankind’s dominion over the material universe.

The historical significance of Christianity’s theological innovation is underrated and difficult to overstate. Long before biotechnology, or even Baconian science, human beings grappled with the obvious tragedy of death. Humans clearly did not need science to engage in philosophical copium and tell themselves that death is, after all, not so bad. From East to West, this is largely what humanity’s poets and sages did.

Christianity alone introduced a singularly hostile view of death as an unacceptable flaw in reality, not an essential part of who we are, and foretold its conquest and obliteration in the Lake of Fire. This victory against death will be won, not in Elysium or the Platonic Realm of the Forms, but in the material universe: in our very bones, our flesh, and in the fabric of the cosmos.

Christianity’s Embrace of the Material Body

A second core innovation of Christianity is its embrace of the human body and the material world. The Christian afterlife is fundamentally immanent and embodied. Christians will not merely go to an abstract “heaven”: instead, all dead Christians will be physically resurrected in glorified bodies—cured of all deformity, sickness, and decay—at the Last Judgment.

In 2 Corinthians, the Apostle Paul explains that, while we long to be set free from the decay of our bodies, it is “not that we would be unclothed, but that we would be further clothed, so that what is mortal may be swallowed up by life.” To be “further clothed” is to receive one’s material “resurrection body.”

Importantly, many people will receive their resurrection bodies without ever having died. Even if no Christians receive their resurrection bodies before the Last Judgment, after all, many Christians will be alive when the Last Judgment occurs. God does not need to kill these living people in order to give them their resurrection bodies. Paul famously observes this in 1 Corinthians 15:51, saying: “We shall not all sleep, but we shall all be changed.” This means that any Christian who wants to argue that death has some positive value cannot even claim that death is a necessary gateway to our resurrection bodies.

The cosmos will itself also undergo a kind of resurrection into a majestic, but still material, form, free of death and entropy. While pre-Christian Judea had a robust doctrine of the Fall of Man, Christians introduced the further idea that the very fabric of the universe had itself been corrupted by the Fall and was decaying. In Romans 8:21, Paul stated that “the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to corruption [or “decay”] and obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God.”

Christianity’s twin claims that our reality had come into being at a finite point in the past and was now “decaying” both contradicted the consensus of Aristotelian physics—that the cosmos is past-eternal, unchanging, and does not decay. In this way, the Christian revelation correctly anticipated something like the Second Law of Thermodynamics and the Heat Death. At the same time, the Bible raised the prospect that creation’s decay could be resolved in the future. Decay does not point to an escape from the cosmos, but to its liberation and transformation: to the creation of “A New Heaven and a New Earth.”

Revelation 21 introduces a vivid cosmography of the future with a divine promise: “Behold, I am making all things new.” It then describes the “New Jerusalem”: a strange, cubical, crystalline structure, comparable in size to the moon, hovering in the heavens. This mysterious imagery has led critical scholar Bart Ehrman to describe Revelation as a form of “science fiction.” The overarching message, however, is clear: God’s new creation will not be an immaterial spiritual world, but a renewed version of this universe analogous to our own resurrected bodies.

In the early centuries of the church, Christianity clarified its view of matter and the body in response to the attacks of the Gnostics: a splinter group who, working to accommodate Christianity to Platonist philosophy, cast matter as evil and denied the bodily resurrection. Irenaeus of Lyon, a second-century bishop thought to be a spiritual grandson of the disciple John, responded to the Gnostics with his work Adversus Haereses—a virtual treatise on the triumph of bodily glory, health, and longevity over aging and death. Irenaeus is today regarded by all Christian denominations as one of the most important fathers of the early church.

In Haereses, Irenaeus worked to systematically refute Gnostic arguments that it was impossible for a biological body to be immortal. According to Irenaeus, Christians must affirm bodily immortality—not an afterlife as a mere immaterial soul—because Jesus Christ has given both “His soul for our souls, and His flesh for our flesh.”

Irenaeus also thinks the Bible teaches that our biological bodies can be sustained indefinitely. He cites stories in the Pentateuch of patriarchs living “beyond seven hundred, eight hundred, and nine hundred years of age.” Regardless, he reasons that “if the flesh were not in a position to be saved, the Word of God [Christ] would in no wise have become flesh.” Irenaeus then concludes explicitly that, by the time of the New Heaven and the New Earth, “man has been renewed, and flourishes in an incorruptible state, so as to preclude the possibility of becoming old.”

No ancient Western system besides Christianity ever suggested that human beings might one day cease to grow old—nor even contemplated human biological immortality as desirable.

In the classical world’s folk mythology, the dead might hope to reside in Elysium or the Isles of the Blessed: an ethereal plane of ease and gentle breezes where the dead strum indolently on harps. In Epicurean philosophy, of course, death represented disintegration and annihilation. Death was, in any case, embraced by classical thinkers precisely as a reprieve from the physical world.

This contrast points to an irony in contemporary atheistic futurism. Today, some techno-accelerationists say that the West has been held back by Christianity’s focus on an otherworldly “heaven” rather than this universe—and that the West must therefore return to pagan morality to get things done. Yet it was only the God of Jacob who gave humanity the messianic vision of a “New Heaven and a New Earth.” Pagans, not Christians, had a pie-in-the-sky Elysium: the Christian God said “I will make all things new.”

The Christian Dominion Mandate and Techno-Optimism

Christianity’s third innovation is its active eschatology, emphasizing human agency in the ultimate conquest of sickness, suffering, and evil. While ancient pagan thinkers speculated about the final fate of the world, they tended to think that large, impersonal laws would determine the universe’s future.

To Christians, however, the coming destruction of death—and the inauguration of the New Heaven and the New Earth—would involve human co-participation with God’s will. In other words, early Christianity prefigured later futurist ideas that intelligence, rather than blind forces, would determine the fate of the universe.

Passages like Psalm 8 articulate a foundational principle of Christian eschatology: mankind’s dominion mandate. The God who has made all of creation, including the stars, has given man dominion over all of creation. “What is man that you are mindful of him?... You have given him dominion over the works of your hands.”

In two of the most iconic parables in the Gospels, the Mustard Seed and the Leaven, Christ prophesies that God’s Kingdom on Earth will grow, fill, and reshape the world. Christians have always understood this Kingdom to be the church, which Paul called the Body of Christ.

Christ’s parables are also allusions to Daniel’s apocalyptic vision in Daniel 2, itself describing God’s people co-participating in the advent of God’s dominion on Earth. This theme eventually reaches its climax in Christ’s speech to John in Revelation, in which “the one who conquers” is invited to share in the water of life and immortality.

In the fourth and fifth books of Adversus Haereses, Irenaeus elaborated on mankind’s dominion mandate and the Christian doctrine of theosis, or divinization: becoming like God. Gnostics argued that the Creator of this material universe must be an evil entity because the world is full of sickness and suffering. In response, Irenaeus argued that Gnostics are only seeing the beginning of the story. By creating humanity, God has germinated the future divinization of this world. Human beings should not “cast blame upon Him, because we have not been made gods from the beginning, but at first merely men, then at length gods.”

Irenaeus is clear that this process of theosis will involve our actively participating with God in conquering the Fall and its effects. Our conquest of decay will itself draw us closer to God, for “the beholding of God is productive of immortality, but immortality renders one near unto God.” Although he could not have anticipated modern biotechnology, Irenaeus plainly has a general notion that we will subdue and utilize the matter of the world as part of our “ripening for immortality.”

The late ancient church father Gregory of Nyssa elaborated on the same essential idea, explaining that God made mankind physically weaker than other animals in order to give us, paradoxically, “a means for our obtaining dominion.”

To make up for our natural deficiencies, Gregory says that humans have been inspired to invent agriculture, domesticate animals, and to develop metallurgy. Our deficiencies have made our own dominion necessary. God permits us to suffer from these deficiencies, not so that we might piously make peace with them, but to refine us, to drive us to transcend them, and to draw us upwards towards Himself.

In John 9, Jesus was asked why a certain man had been born blind from birth. “Who sinned, this man or his parents?,” Jesus’ disciples ask. Jesus does not say—as a modern pietist might—that God wishes the blind man to learn inner peace through suffering. Instead, he responds that the man was born blind so that “the works of God might be displayed in him.” Jesus then heals the man’s blindness by anointing his eyes. “We must work the works of him who sent me,” he tells his disciples.

In other words, blindness—as Irenaeus and Gregory suggested—only exists as a limitation to be overcome. Jesus’ teaching, as well as the example of his healing ministry, inspired Christians to invent the first hospitals and drive the advancement of medicine and the sciences throughout history.

Modern Christian apologists often argue that Christianity, with its faith in a universe of fixed and elegant laws, laid the intellectual foundations that made science possible. Yet Christians did not drive the progress of science simply because their descriptive metaphysics allowed it: they were also driven to discover, innovate, and build because they were ablaze with a holy imperative to take dominion over the universe and subordinate it towards the flourishing of mankind. This was palpably true of, for example, Hildegard von Bingen, Roger Bacon, Johannes Kepler, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, and Pasteur.

How Christianity Created Tech Futurism

What is now sometimes called “futurism”—an active, technological, and optimistic vision of humanity’s role in the universe—was first espoused by Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic theologians in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Today, some staunchly atheistic futurists attempt to omit Christian thinkers from the lineage of futurism. These futurists prefer to trace their ideas to a 1929 book by the Marxist futurist JD Bernal or, before him, to a 1924 essay by JBS Haldane. Yet the Eastern Orthodox theologian Nikolai Fyodorov explicitly advocated both space colonization and regenerative biotechnology from 1864 until his death in 1903.

Fyodorov is a theologian of monumental but understated influence. Known as “Moskovskii Sokrat,” he attracted a circle of influential disciples in Moscow, including Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, and taught that God was calling upon humanity to extend itself throughout the universe, command matter, conquer all bodily decay, and regulate the forces of the cosmos. Tsiolkovsky would one day be known as the father of rocketry.

The Catholic priest and paleontologist Teilhard de Chardin expressed similar ideas in his seminal work Writings in a Time of War, written while serving as a wartime stretcher-bearer from 1916 to 1919. The book contains the greatest essay of Teilhard’s career, Cosmic Life, in which Teilhard proposes that we may “envisage a new era in which suffering is effectively alleviated, well-being is assured, and—who knows?—our organs are perhaps rejuvenated.” Teilhard warns that “It is dangerous to challenge science and set a limit to its victories, for the hidden energies it summons from the depths are unfathomable.”

Teilhard has been positively quoted by multiple popes, including Paul VI and Benedict XVI, and was once described by Pope John Paul II as “a man seized by Christ in the depths of his being.” His ideas were also endorsed by Pope Pius XII in a magnificent 1939 speech entitled “Man Ascends to God by Climbing the Ladder of the Universe,” expressing many of the concepts discussed in this essay.

Secular futurist philosopher Eric Steinhart notes that even secular futurists “work within the conceptual architecture of Teilhard’s [futurism] without being aware of its [Christian] origins.” It is not a coincidence that futurism was first espoused by Christians rather than Marxists, Buddhists, or any other group. Both materially and spiritually, messianic monotheism and the Christian resurrection planted, at the axis of the ancient world, the germ of a war against death.

What Does This Mean For Us Today?

Constantine’s war is being fought now. Today, Christians are undernoticed among the innovators, builders, and leaders who are fighting to combat suffering and promote human flourishing through ethical biotechnology. For example, Christians are playing a leading role in the legal and policy battle to unleash regenerative biotechnology in the United States.

As of this writing, three states in the United States have innovative legal regimes allowing patients to effectively access experimental biotechnology parallel to the normal Food and Drug Administration pathway: Montana, New Hampshire, and Florida. In both New Hampshire and Florida, the push to pass the law was led primarily by conservative Christians, with secular organizations and businesses playing a supporting role.

The modern regulatory state has created major obstacles to technological progress. The examples of New Hampshire and Florida show that Christians can use our energy and organizational skills to dismantle these obstacles. By doing so, Christians are combatting evil, worshipping God, and carrying out our dominion mandate.

In New Hampshire, where my own work is focused, Christians hope to set an example that can resonate throughout the country. Our new law is just the beginning. New Hampshire’s proximity to Boston’s biotech hub, together with our unique political culture, put our state in a prime position to become a leading center of experimental biotechnology. By leveraging these advantages, we can unleash a flourishing industry in the state and help to combat the evils of sickness and decay in New England and across the country.

I began my legislative testimony in favor of New Hampshire’s law by discussing Jesus’ healing ministry and his call for us to imitate his example. In the light of Christ’s life, no knowledgeable legislator—Christian or secular—can be surprised that a Christian would support biotechnological progress.

Faithful Christians must continue to heed the call of Christian theology to advance science and technology—both by removing obstacles to their advancement and by taking leading roles in these fields. Non-Christians who work in technology and science should also reconsider Christianity’s role in promoting the sciences and the role that Christians can play today in unleashing them. Constantine’s “battle for deathlessness” continues.

Contact me if you are a Christian church leader or advocate who wants to discuss how the church can promote ethical pro-biotech legal reforms—or a biotechnologist who wants to discuss the role of Christianity in advancing human flourishing. You should also contact me if you’re a leader in science and technology interested in making use of New Hampshire’s enabling environment for regenerative medicine and biotechnology.

“It was necessary that man should in the first instance be created; and having been created, should receive growth; and having received growth, should be strengthened; and having been strengthened, should abound; and having abounded, should recover [from the disease of sin]; and having recovered, should be glorified; and being glorified, should see his Lord. For God is He who is yet to be seen, and the beholding of God is productive of immortality, but immortality renders one near unto God… We cast blame upon Him, because we have not been made gods from the beginning, but at first merely men, then at length gods.”

— Irenaeus, Adversus Haereses, IV.38

Ian Huyett is a litigator and lobbyist who writes on law and technology. Follow him on X @IanHuyett.