The Five Big Challenges for Startup Society Founders

Part 1/2 - Your airplane read for the Network State Conference in Singapore (here). Join us in the Draper House during Token49 (Oct 1-2) to dive deeper into these lessons (here).

By Niklas Anzinger

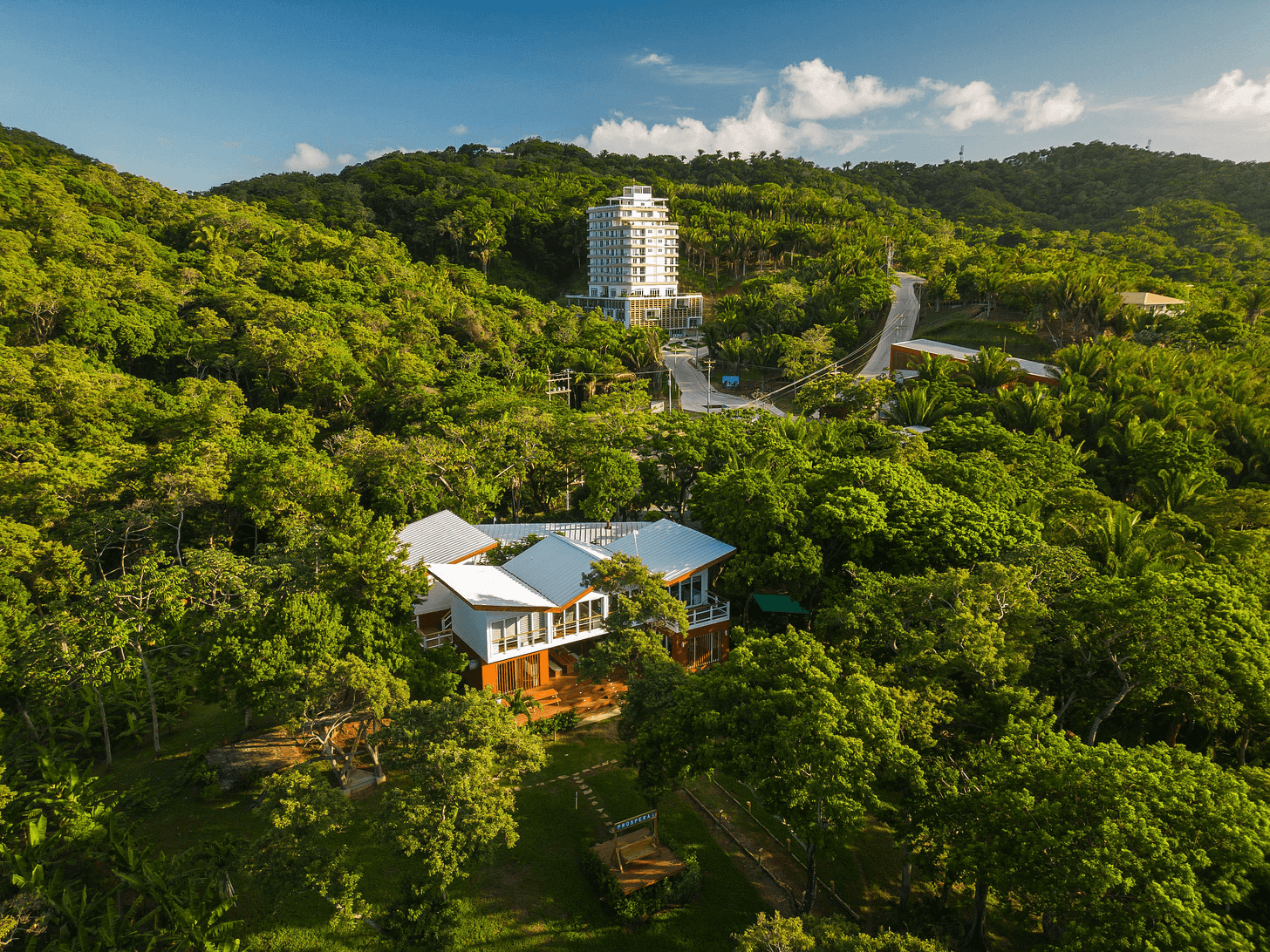

I’ve been working in this odd “industry” for the past 3.5 years. These lessons come from building Infinita City (a longevity-focused network society Layer 2), investing through Infinita VC, and serving as both an advisor to and resident in Próspera.

Building a real-life jurisdiction is hard. There’s little best practice, no clear playbook, and no repeatable business model. The closest we have is Balaji Srinivasan’s The Network State. Many readers don’t find it very practical, but I think it contains deep, original ideas (I’ll return to them in Part 2). Another reference is Mark Frazier’s Founding Startup Societies, comprehensive, with multiple possible directions, but difficult to distill into a standard practice, especially for a tech-driven approach.

To be sure we’re talking about real-life jurisdictions - not a Discord server, a Metaverse project, or an “online city”. There has been a wave of projects that seem to have misunderstood that part. As Balaji puts it: “Online first, land second, but not land never.” Some projects, like Próspera or Ciudad Morazán, started with land. Others, like Balaji’s Network School, began online to prove an alternative. These approaches are somewhat in conflict (more below), and neither is necessarily better - it depends on your starting conditions. In the end, you have to bring it together.

(It’s hard to think of a state or jurisdiction as a business model. But it is one, and you have to accept that framing for now. As a primer, check out this podcast with Patri Friedman.)

At the core, every founder needs to get three things right at the the same time:

·Demand: a group of people willing to move & populate the place

·Infrastructure: basic amenities for people to live and work in

·Jurisdiction/Legal Autonomy: the ability to make your own rules

No project has gotten all three right from the start. Here is a comparison of some major projects and their starting points:

Project: Próspera

Demand: Medium to weak

Model complex. Emerging as hub for founders, local entrepreneurs, affiliates. Growth slow but steady.

Infrastructure: Medium

Beautiful location, infrastructure nearby, but slow buildout. High bar for amenities.

Jurisdiction: Very strong

Scalable legal code, superior to first-world regs (medicine, finance, crypto). Proven and defended successfully.

Project: Ciudad Morazán

Demand: Strong

Clear thesis: blue-collar Hondurans. Value prop proven; manufacturing demand unproven.

Infrastructure: Strong

Delivered minimal viable infrastructure: housing, community space, church, stores, schools. Not attractive to first-worlders.

Jurisdiction: Strong

Autonomous low-complexity model. Hasn’t asserted rights much; less sophisticated by design.

Project: Network School

Demand: Medium to strong

Balaji’s influence drew thousands; proven scale; stickiness TBD.

Infrastructure: Very strong

Forest City, Malaysia: real estate solved for a decade; easy move-in for small biz.

Jurisdiction: Weak

SEZ with tax perks; lacks rule-making power. Test for demand-first thesis.

Project: Itana

Demand: Medium to strong

Clear value: African tech workers; strong local fit.

Infrastructure: Medium to weak

Own compound stalled; repositioned as digital jurisdiction.

Jurisdiction: Medium

SEZ under Nigerian state; Delaware-like domicile possible but heavy lift.

Note: this isn’t a judgment or ranking of these projects, just observations of the challenges they face.

The table shows how hard it is to get all three right. I’ve argued before that there are inherent trade-offs between jurisdiction and demand. To build demand, you need to be loud and visible, and that often requires a contrarian bent (think Bryan “look at my Johnson” Johnson). But being loud and contrarian doesn’t help with government negotiations, and it can make land acquisition harder.

Example: Solano County in California bought land in secret. If its big ambitions and funders had been known, prices would have skyrocketed. Demand there still isn’t proven.

The Five Big Challenges

Let me unpack a bit further what concrete challenges await any startup society entrepreneur who aims to eventually build on-land, regardless of the initial strategy.

#1 Political Stability

There’s a catch-22: the countries most open to granting legal autonomy are often the least politically stable. Corruption and instability come with the territory.

Critics often say, “the country can just shut you down.” That’s premature. Sure it’s a risk. But Singapore, Dubai, and Hong Kong were all fragile in their early years, they only look inevitable in hindsight.

The practical problem with instability is that it bogs the leading organization down in diplomacy. You want to build, but instead you’re forced to argue. Honduras under the socialist Castro administration is a case I know from lived experience. Political events in Próspera often force us to drop everything and react to pressure. It slows progress.

#2 Reputation Building

By default, you have to build a challenger coalition inside the host country. Established figures have little reason to support you, they’ve already done well under the old order.

What you need are champions with ideological motivation to challenge that order, and enough allies who stand to gain from positive-sum change. But these people are usually under-resourced: limited reputation, weak fundraising ability, or have a lobby in existing power structures.

The upside: this can be hacked. It’s the same challenge every disruptive startup faces. Think of early crypto, Uber, Airbnb, or PayPal, they all started as mavericks.

#3 Capital Needs

Land and real estate returns are structurally different from software or venture. VC bets on high-risk, high-upside opportunities; real estate is low-risk, low-upside.

One option is capital-light land strategies (like leasing). But then you miss the upside of value appreciation. That’s a big part of why WeWork collapsed: recurring lease costs without upside capture.

The land problem: the more you acquire upfront, the more upside you capture later. But that also locks capital unproductively, money you could have used for tech or business development. That’s inherently startup-unfriendly.*

*Note: this is part of why I’m so bullish on Honduras. Normally, you need $100m+ to get a one-off deal with a government. Honduran SEZs let you start lean: join the SEZ framework with minimal land, then expand through voluntary acquisition.

The real estate problem: outsourcing to third-party developers looks tempting, but it doesn’t separate the risk profile. You’re still offering venture risk with real estate returns. Maybe the downside isn’t zero, but it often means legal complexity and court battles. In the early stage, you’ll probably have to do real estate yourself.

#4 Talent Availability

There is a simple distance model for your ability to attract people to come: the higher the switching cost or the further the geographic and cultural distance, the less likely people are to move.

If people live nearby and have little to leave behind, they’re more likely to come (Ciudad Morazán proved this). The further away they are, culturally or geographically, and the more they’ve achieved in their current setting, the less likely they’ll uproot. Families and reputations raise the opportunity cost: you’ve already invested heavily in one environment, and starting from scratch is harder.

The default strategy is to tap local talent pools. To some extent this is inevitable (see #5) and even lucrative (lower wages, higher commitment). But you’re building a high-risk, high-upside venture. That’s why large pools like SF or NYC have an inherent advantage: more exceptional, specialized talent. Locally, that’s harder to find.

There are ways to work around this. My view: the sweet spot isn’t big countries like Brazil (political change is too hard), or tiny sovereign islands (too little talent). It’s medium-sized countries, Honduras, Argentina, Malaysia, where the pool is large enough to find exceptional talent. Islands within these states (Roatán in Honduras, Langkawi in Malaysia, maybe Zanzibar or Florianópolis) can be ideal: some insulation from political noise, plus relative tranquility.

#5 Local Employment

Local employment and growth are your social license to operate. If you’re cut off from the local economy, you’ll face resistance and lack political defense against capture.

The catch: talent that matches your industry focus is often scarce. If the sector already produced enough of it, there’s little incentive for you to enter.

That means you’ll have to train local labor, often starting from a gap in cultural or professional skills needed for a high-risk, high-upside venture.

You probably don’t want to be seen as a foreign enclave, unless you have exceptionally strong political backing (Dubai can host a majority-foreigner population, but that’s rare). That’s why you need to invest early in talent upskilling.

The Road Ahead - What Can Give You A Unique Edge?

Many of these lessons aren’t unusual for startups, but this is hardcore mode. If SaaS is easy, crypto/biotech are medium, and hardware is hard, then building a startup society is a level above. Still, there should be a learning curve, something we’ll see at the Network State Conference. Study the projects and draw your own lessons.

At minimum, you need to think hard about your edge. Somewhere in the holy trinity of demand, infrastructure, and jurisdiction, you need a decisive advantage:

Demand:

Can you capture the attention of millions?

Is there a clear local need or pull factor for migration?

Are you positioned at a moment of large-scale shifts?

Infrastructure:

Do you have unique access to dormant real estate?

Do you have experience or connections to build fast?

Do you have a strong land deal in hand?

Jurisdiction:

Do you have political champions, ideally across several countries?

Do you have resourceful local lawyers to navigate the landscape?

Do you personally understand constitutional and international law?

I chose to build Infinita City in Próspera, because I see jurisdiction is the limiting factor. This is where most of the upside lies. But it requires founders to understand this area of law. A superficial understanding or relying solely on a lawyer won’t cut it. You need to understand it deeply. Long-term success depends on it.

My biased call to action: rally around Próspera. It’s the jurisdictional zero-to-one. If we succeed there, especially with the November 2025 elections in Honduras, every other project gains a stronger defense and strategy.

This entire article is way too biassed. infinita giving a perspetive on new real estate developments is not going to be a realistic nor balanced perspective on the reality of real estate development. it's like listening to balaji.

you are sales people pretending to be unbiassed analysts.

why? this only gets fewer people to trust you and acts as a filter for the true believers to join your cult.

if you want quality people and quality decisions, you'll just accept you are like a hotel or time share salesman. and stop with the nonsense. my sincere opinion, to help you succeed. drop the pretense.